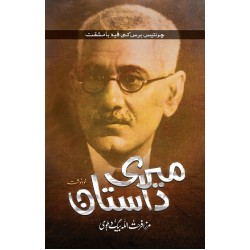

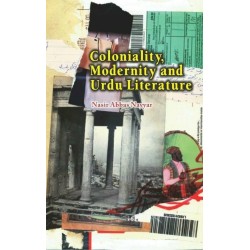

- Writer: Nasir Abbas Nayyar

- Category: English

- Pages: 250

- Stock: In Stock

- Model: STP-14907

I present this English translation of Postcolonial Perspectives in Urdu Literature—originally published as مابعد نوآبادیات: اردو کے تناظر میں (Māba‘d Nawābādiyāt: Urdū ke Tanāzur Mein; also rendered as Mabad Nawabadiyat: Urdu ke Tanazur Mein)—by the eminent scholar and critic Nasir Abbas Nayyar, with admiration and respect. First published by Oxford University Press in 2013, the book has shaped contemporary debates in Urdu literary studies, bringing postcolonial questions of history, identity, and language into sustained conversation with Urdu’s critical traditions.

Translating a postcolonial critique into English—the very language once enlisted in colonial governance—carries an undeniable irony. Yet that tension is instructive. It reminds us that thought survives borders, and that rigorous scholarship must travel across languages if it is to participate in a genuinely global discourse. In bringing Nasir’s insights to Anglophone readers, this translation hopes to serve both as a bridge and a provocation, inviting renewed reflection on the afterlives of empire.

The work of translation here has been as much intellectual as linguistic. Nasir’s prose is precise and allusive; his arguments are finely layered. I have sought fidelity not only to his vocabulary and cadence but to the movement of his reasoning—preserving key terms and conceptual nuance while keeping the English readable and coherent. Where unavoidable, I have retained certain Urdu and Persian critical terms in transliteration, briefly glossed at first occurrence.

This rendering can only be an approximation of the original’s richness, but it is offered in the spirit of dialogue: with the author, with Urdu criticism, and with readers encountering these debates in a new idiom. If the text unsettles easy assumptions, prompts careful thought, and—now and then—elicits a wry smile at the paradoxes of language and power, it will have honored its source.

Omair Ahmed Khan

October 21, 2024

------------------------------

The second edition of this book emerges a decade after its original publication, and for that, one can only be grateful. It has avoided the fate of those works that, upon or shortly after their release, begin their journey into oblivion—books whose lives can be aptly described with the metaphor of a bubble. Throughout these ten years, this book has been read consistently, if not always in abundance, and it has continued to stir an awareness of the necessity of postcolonial studies in Urdu literature. Whether this awareness remains robust or tenuous, however, is for the readers to decide.

It must be acknowledged that before this book saw the light of day, the seeds of postcolonial critique in Urdu were scattered but present. Progressive literary criticism touched on the political and economic exploitation of colonialism, while traditionalist critique examined its cultural oppression—many of those discussions still retain their relevance. Likewise, there were those acquainted with the works of postcolonial theorists like Frantz Fanon, Edward Said, and others. Some had immersed themselves in the writings of Eqbal Ahmad, while notable efforts had been made in Urdu to study the literature of Black and Dalit communities. Traces of colonial influence could even be found in a few essays analyzing key writers of the 19th century. In addition, during the closing years of the 20th century and the dawn of the 21st, postcolonial discourse made occasional appearances in broader theoretical debates.

Yet despite all these indications, postcolonial criticism in Urdu literature had not crystallized into a coherent, organized tradition. These were mere hints, scattered like pieces of a puzzle yet to be assembled. There was no single, comprehensive volume that drew these disparate threads into a unified whole.

It could be asked why, immediately after gaining political independence from British colonial rule in 1947, we did not make concerted efforts towards a comprehensive decolonization of our educational, constitutional, administrative institutions, as well as our language, literature, and cultural sectors. In the post-independence writings, there is abundant mention of the British Raj, colonialism, slavery, the freedom struggle, and its leaders; lamentations about the fractured dawn of independence; attempts at defining cultural identity; and questions regarding the emergence of a distinct literary identity for Pakistan. Yet, one barely encounters a deliberate dissection of the economic and cultural exploitation of colonialism, nor a structured discourse on the institutions and ideologies that facilitated such exploitation. The absence of this discourse is felt more acutely today, raising several pertinent questions.

Was it because our political leadership prioritized the construction of a religious state, embracing a concept rooted in defining itself against a "foreign Other"—namely, the Hindu? Was that the reason why, instead of liberating all facets of life, including language and the arts, from colonial influence, we busied ourselves with purging every domain of life from perceived Hindu elements? Why, instead of dismantling the colonial legacies that pervaded our institutions, were we obsessed with battling the phantoms of an enemy born from that very colonial era?

Today, this poses a serious question for us: why did our intellectual and creative endeavors gravitate either toward purging our mental and imaginative worlds of this constructed 'Other' (Recall Manto's "Allah Ka Bara Fazl Hai," written immediately after independence), or toward narrating displacement and migration, seeking its historical and religious roots, and indulging in revivals of bygone eras? Did history leave us with no other path? The little remaining energy was spent contending with military dictatorships, leaving little room for alternative pursuits

The fundamental question arises: Was everything that transpired during 1947 and immediately after merely coincidental, or was it shaped by a historical process? Who crafted the map of the world we were forced to endure? No discerning individual would accept that the events of collective life are mere accidents; they occur due to historical causes. Why, then, did we fail to comprehend the colonial history that shaped us, and why didn’t we make any serious effort to free ourselves from its lingering effects? The riots of 1947, one of the greatest tragedies not just of South Asia but of human history, beg the question: why did such a calamity not occur earlier? It is understandable to revere national and religious identity over human identity, but who will explain why this sacred identity became so deadly?

Our literature, which in its classical period had continuously highlighted the lethal potential of religious and national identity, why did a significant portion of that very literature come forward to solidify and justify this identity? In post-independence Urdu criticism, the classical era was referred to as the Indo-Islamic civilization. Strangely, attempts were made to revive it, but only at a verbal level, not at conceptual or ethical levels. Why? The term "Indo-Islamic civilization" was used to either bring forth writings that predominantly represented the fundamental concepts of a single religion or to focus critical intellect on discovering metaphors, meanings, and stylistic devices. Yet, the satirical critique of religious and social hypocrisy found in the literature of this civilization, particularly in ghazal poetry, where love was elevated as the highest human value and inner freedom expressed through a wild defiance of fate and nature, was rarely acknowledged or revived.

In truth, the exceptional concept of nationalism born during the colonial era—always defining itself against 'the other'—overshadowed both our understanding of the past and our expression of the present. The discussions about Pakistani civilization have stemmed either from agreement with or rejection of this concept, or an attempt to distance oneself from it. The intellectual and creative endeavors of the last seventy-six years have been intertwined in a constant negotiation with this idea. Can we move beyond this negotiation? I believe we can, but only when we truly undertake the task of decolonization—gaining a true understanding of colonialism and liberating ourselves from its constructs. These constructs have seeped not only into our literary historiography but into our collective imaginations, values, and standards.

Even today, we encounter individuals who consider the colonizer to be the greatest benefactor in the history of this land. They point to modern technology and educational and administrative institutions as evidence. The reality is that the greatest success of the colonial enterprise was the comprehensive exploitation of this land, the unravelling of its social fabric, the laying of a long trail of conflicts, and the genocide of its people through famines and riots, all while positioning itself as a benefactor. As for the railway, the telegraph, and other such advances, these are scientific inventions that would have reached the world anyway, in their own time. The real question is: how much benefit did these technologies provide to the native Indians, and how much did they serve the interests of the British? How much convenience did the railway offer to the local populace, and how much did it facilitate the swift transportation of raw materials and soldiers to distant regions for British industries?

A simple question is this: if the British were truly benefactors, why did the leaders of our independence movements find it necessary to fight against them? Finally, let us not forget that there is a difference between colonial modernity and modernity itself. Forgetting this difference leads to numerous misconceptions.

The questions raised above have not only been the driving force behind this book but also inspired subsequent works, particularly Cultural Identity and Colonial Hegemony, The Reconstruction of Urdu Literature, and Modernity and Colonialism.

In this edition, a new essay has been added. Racism, as one of colonialism's most potent and destructive weapons, has played a significant role in shaping both societies and literatures. This essay delves into the poetics of racism and explores its multifaceted expressions in literature, now included as a dedicated chapter in this book.

The first edition of this book was published by Oxford, and I extend my gratitude to Sang-e-Meel for bringing forth this second edition.

Nasir Abbas Nayyar

Lahore

May 15, 2023

| Book Attributes | |

| Pages | 250 |